Summary

-

The underlying performance for the major banks was solid for the first six months of fiscal 2020 (1H20). Operating income was broadly stable half-on-half as largely flat net interest margins were met with soft, yet still positive, volume growth.

-

Performance will soften in the near-term as mortgage and other loan deferrals take effect in response to a rising number of furloughed individuals, although government support to date appears to be filling the gap left by a loss of income due to a lower number of hours worked. Provisions (credit losses) rose sharply in an attempt to reconcile with an uncharted outlook-a government-enforced shutdown, which is temporary in design, but whose impact will likely persist for years.

-

Further provisions may indeed be required as current levels are well-below those raised in the early 1990’s when unemployment was last in double-digits. However, the composition of unemployment and unprecedented levels of forbearance and support from both lenders and the government is likely to temper that need, somewhat.

-

Capital preservation was the main focus as ANZ and Westpac took the unprecedented step of deferring payment of ordinary dividends to shareholders (NAB reduced its dividend by more than 60%). Although we expect dividends to resume in 2H20, we would not view as a base case that shareholders will recoup the deferred component. We would also not rule out further capital raisings, which would clearly benefit creditors.

-

The major banks provided base case and downside economic scenarios (year-end estimates for unemployment, output and house prices) and the impact of those scenarios and estimates on their respective regulatory capital ratios (a measure of their solvency).

-

The scenarios and estimates provided are not designed to provide a false sense of precision. However, they do provide us with a view of the capacity to absorb further provisions, if required. On this basis, we believe the major banks would have sufficient levels of capital to absorb a further increase in provisions as envisaged in modelled downside scenarios.

-

Given the capital headroom above the point at which an issuer would be required to either write-off or convert some or all of its subordinated debt to common equity, we believe the more severe risk to creditors of either deferred coupons (in the interim) or conversion/write-down of principal at a later point is very low. As such, we remain comfortable with major bank debt-Tier 1 hybrids and Tier 2 subordinated debt.

1H20 results: solid, bar a few 'own goals'

Credit fundamentals for Australia’s banking sector provide a strong starting point leading into the COVID19 induced slowdown.

Despite a few ‘own goals’, including further provisions for customer remediation stemming from the Royal Commission (now standing at more than AUD8.5bn across the four major banks by our count), provisions for regulatory penalties (as Westpac fell short of expectations on compliance with anti-money laundering obligations) and write-downs, underlying performance was solid for the first six months of fiscal 2020 (1H20). Australia’s major banks benefit from a high proportion of earnings with recurring characteristics, with net interest income (customers repaying their loans, net of the cost of bank funding) accounting for ~75% of operating income (revenues).

Net interest margins were largely stable (see Figure 1), as mortgage repricing offset higher funding costs (although the cash rate and interbank funding rates have fallen, there is a delay in which banks realise that benefit for term funding). Volumes were generally softer as households continue to deleverage, and while business volumes were stronger, much of this likely stemmed from companies drawing down on existing facilities in anticipation of the impending slowdown. The product of relatively stable margins and positive volume growth was a broadly stable level of operating income in the first half (see Figure 2).

Unsurprisingly, the near-term outlook is clouded with significant uncertainty. The decision to reduce and indeed defer dividends to shareholders in some cases is an acknowledgment of such uncertainty. Performance will undoubtedly soften in the near-term as mortgage and other loan deferrals take effect, while non-interest income faces considerable headwinds. Provisions have been raised in an attempt to reconcile with an uncharted outlook-a government-enforced shutdown, which is temporary in design, but whose impact will likely persist for years. Further provisions may yet be required. Attention must now turn to the balance sheet, and the capacity of the major banks to absorb the forementioned headwinds.

Uncertain economic outlook drives increase in provisions as hours worked collapses

The greatest challenge posed by COVID-19 was to keep individuals gainfully employed (or at least subsidised in lieu) while remaining housebound and observing social distancing. While the headline unemployment has indeed increased, it was to a lesser extent than had been anticipated, despite ~600,000 individuals losing their jobs (the denominator, labour force was lower as individuals simply stopped looking for work). Recall too that individuals on the governments wage subsidy program-JobKeeper-are not classified as unemployed, even if they have been furloughed.

The underlying figures highlight the depth and severity of the slowdown to date, with underemployment rising sharply and hours worked collapsing (see Figure 3). The underutilisation rate, which measures the extent to which all available labour force resources-unemployed and underemployed-are not being fully used in the economy is at its highest level since records began (see Figure 4), and most notably, if not overly unsurprisingly, for younger demographics (15-24).

The unemployment rate is likely to shift higher as individuals on government subsidies-principally JobSeeker-re-enter the labour force, and as other government subsidies are wound back. And that remains the greatest area of uncertainty; the income shock to highly leveraged households when unprecedented levels of government support (see Figure 5) are wound back and mortgage repayment deferral arrangements expire (see Figure 6), for both households and small business.

Figure 7, which includes JobSeeker payments (and which have principally benefited younger age groups who were likely to be casually employed and the first casualties of this downturn [highlighted]) but was measured prior to JobKeeper payments commenced (which will support older age groups in the coming months), suggests the level of government support is filling the gap left by a loss of income due to a lower number of hours worked.

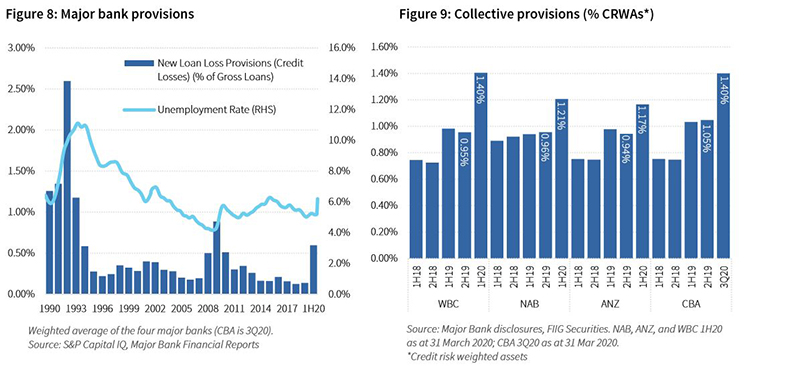

In prior recessionary periods (the early-1990’s and the GFC more recently [technically not a recession save for population growth]), corporate and commercial property loans were the primary driver behind increased provisions (credit losses) (see Figure 8). Whether through an inability to refinance or poor lending practices, losses were relatively easy to recognise, even if late in the piece (and near fatal for Westpac and ANZ in 1992). Under prior accounting regimes, credit losses were recognised only once there had been an incurred loss event.

This time around, the current risks revolve around households, which make up close to two-thirds of bank loans, and whose employment and income prospects face the real risk of a negative shock for a prolonged period of time. Against this backdrop are historically high levels of household leverage (although the interest component has reduced considerably following central bank intervention early in the onset of the crisis).

This time around, the current risks revolve around households, which make up close to two-thirds of bank loans, and whose employment and income prospects face the real risk of a negative shock for a prolonged period of time. Against this backdrop are historically high levels of household leverage (although the interest component has reduced considerably following central bank intervention early in the onset of the crisis).

Current accounting standards introduced in 2018 shift the emphasis from incurred loss to expected credit loss (ECL). As such, provisions are sensitive to the economic assumptions that are made and what weighting is assigned to each scenario. ECL’s are derived from the following inputs:

- A probability weighted average of three scenarios-usually a base case, upside and downside; and

-

Management adjustments for emerging risk at an industry, geography or segment level.

Download the Deloitte Corporate Bond Report

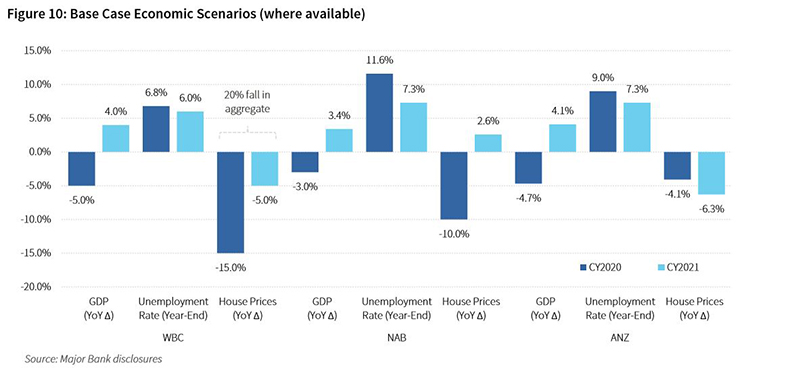

The probability of each scenario is determined by considering relevant macro-economic outlooks and their likely impact on the bank’s credit portfolios. Figure 10 provides estimated base case scenarios as provided by the major banks (where available) (Figure 12 further below provides provision estimates across a base case, upside and downside scenario). As the figure below highlights, a significant degree of variance exists across the three banks, particularly the impact of the current downturn on property prices (hence the substantial increase in collective (rather than specific) provisions [see Figure 9]). Given the uncertainty around the depth and breadth of the current downturn, this is perhaps of little surprise.

Dividend flexibility supports capital, but unlikely banks will need to adopt more severe measures

ANZ and Westpac took the unprecedented step of deferring payment of ordinary dividends to shareholders (NAB reduced its dividend by more than 60%). While there is no shortage of inference about the use of the term ‘defer’ (although we suspect the deferred component may never be recouped, we do expect dividends to commence later this year-see below), it is worth reiterating that dividends are optional distributions of excess earnings; first and foremost, they provide a buffer to absorb losses.

Bank capital represents the capacity to absorb losses (i.e., remain solvent). Regulators specify the minimum amount of capital that banks should allocate against various risks. Of particular importance is the amount of capital allocated against credit risk-the risk that borrowers will not repay their debt obligations-as this is typically the main risk that commercial banks assume. Banks are required to determine the capital to allocate against their credit exposures by assigning each class of credit risk exposure a ‘risk weight’ that reflects the potential for unexpected losses. The product of this assessment is a risk weighted asset-the denominator in a bank’s regulatory capital ratio.

The riskier the asset, the higher the risk weight, and the greater the amount of capital required to maintain minimum capital (solvency ratios). As asset quality deteriorates (in this downturn, think rising unemployment, increasing arrears and falling property prices-both residential and commercial), the probability of default and loss given default also rises-albeit, with a lag. This increases the risk weighted assets, which reduces the capital ratio (all else equal). This relationship also demonstrates the pro-cyclicality of capital ratios-during periods of stress, the denominator increases and the ratio deteriorates (all else equal). While regulators will therefore prescribe additional requirements to counter this from time to time, banks will also set aside additional capital (provisions), as they have done by reducing or indeed deferring dividends.

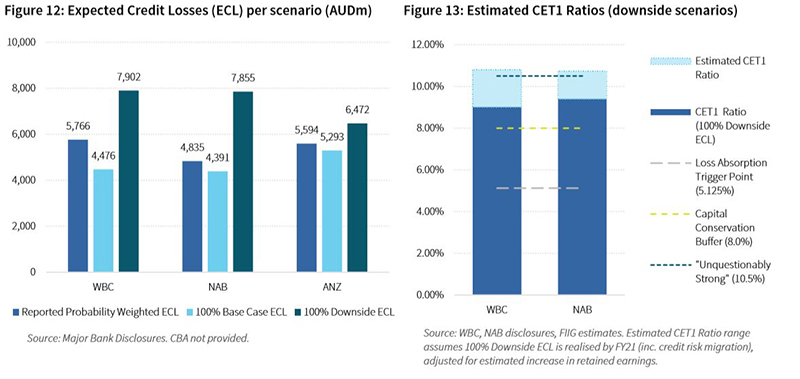

Figure 11 demonstrates CET1 sensitivity to credit risk weighted asset migration over two years in response to modelled economic scenarios, as provided by the banks during their respective trading updates. Across the four major banks, credit risk weighted asset migration in response to a base case is ~95bps (of CET1 reduction) (loosely, a “V-shaped” recovery) and ~175bps for the downside scenario (a more protracted recovery) (ex-ANZ, which did not disclose CET1 sensitivity to credit risk weighted asset migration in a downside scenario).

Figure 11 only demonstrates the sensitivity of the denominator (credit risk weighted assets) in a bank’s capital ratio. For example, a downside case for NAB would require a further increase in credit loss provisions of ~AUD3.0bn (all else equal), with Westpac requiring a further top-up of ~AUD2.1bn (see Figure 12). This would have the effect of reducing the numerator-capital.

However, these scenarios cover a period of two years. Given the earnings generation capacity of the major banks (see Figure 2), we believe organic capital generation (retained earnings) would be sufficient to absorb a further increase in provisions as envisaged in Figure 12 (see Figure 13 for WBC and NAB).

For completeness, the scenarios and estimates provided above are not designed to provide a false sense of precision (second- and third-order effects are very difficult to model). However, they do provide us with a view of the capacity to absorb further provisions, if required. APRA has provided flexibility for banks to utilise some of their capital buffer during this period, which is likely to see them fall below the 10.5% ‘unquestionably strong’ benchmark (not a regulatory minimum, but rather a target). The duration of this forbearance is likely to have some bearing on the ability and willingness of recommence dividend payments to ordinary shareholders. At present, our base case is as follows:

-

Further provisions are likely, owing to the income shock from households as government subsidies are wound back;

-

Dividends are likely to resume in 2H20, but we would not view as a base case that shareholders will recoup the deferred component; and

-

Further capital raisings should not be ruled out.

By extension, given the headroom above the Loss Absorption Trigger Point of 5.125% (see Figure 13)-whereby APRA can instruct an issuer to either write-off or convert some or all of its Tier 1 Hybrids into Common Equity-we believe the more severe risk to creditors or either deferred coupons or conversion/write-down of principal is very low. While we believe there is a reasonably good chance the rating agencies could lower the ratings across the capital structure by a notch if even a base case were to materialise (see Figure 9), we remain comfortable with major bank debt-both Tier 1 hybrids and Tier 2 subordinated debt.